Theatre's war against whoonga by Lloyd Gedye

Click here for original post, published and written for City Press

Can theatre change lives?

Lloyd Gedye spends time with the creators of an extraordinary new play, Ulwembu, born of the life stories of whoonga (nyaope) users in KwaZulu-Natal communities. He comes away believing in the power of the stage

Lloyd Gedye spends time with the creators of an extraordinary new play, Ulwembu, born of the life stories of whoonga (nyaope) users in KwaZulu-Natal communities. He comes away believing in the power of the stage

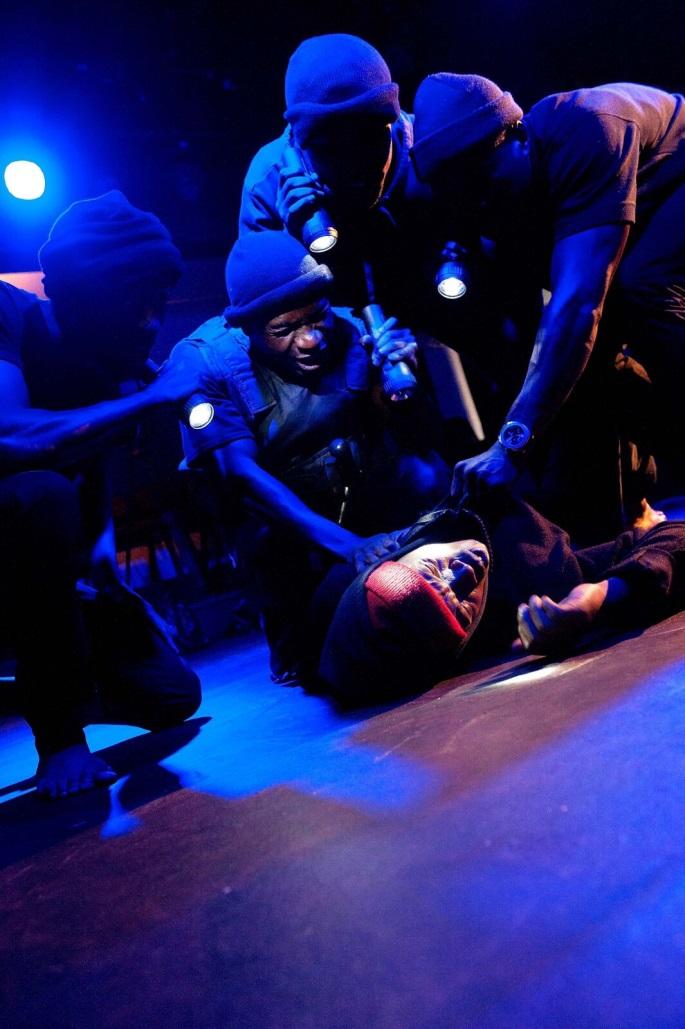

‘They died in front of my eyes,” says Phumlani Ngubane as we sit in the foyer of the Durban Playhouse’s Loft Theatre. “They were shot. They stole from a bad person who hunted them down. They were murdered right in front of my eyes ... My heart is pained, even now.” His colleague Zenzo Msomi nods solemnly as Ngubane speaks and then adds: “We were like family with them. They stole from the wrong house.” Actors Ngubane and Msomi are part of a KwaMashu theatre collective called The Big Brotherhood, and on the day we sat down to chat in mid-April, they were in the middle of a run of their play Ulwembu (Spider) at the Loft Theatre.

The play’s focus is the scourge of whoonga – or wunga, or nyaope, as it is known in other parts of the country. The play is based on more than two years of deep research and the couple who were murdered were Ngubane’s landlady and her boyfriend, both whoonga users. “Some people in my community turned against me, as I was associated with the users,” says Ngubane. “They felt like I was defending them.” Ulwembu is a gritty urban nightmare, a place where characters mostly on the margins of society eke out lives, rather than live them. It is a story about addiction, featuring drug users, runners and dealers, desperate mothers, absent fathers, helpless and vindictive police, overworked social workers, enraged communities, fearless xenophobes and foreign nationals living in fear. It effortlessly illustrates how everyone in a community is drawn into the web of whoonga. Large ropes pulled by the whole cast to contort around the users as they go into withdrawal represent this web.

...

At R25 a hit, whoonga is one of the cheapest drugs around and, for dealers, it’s a big-money industry. The Big Brotherhood’s research suggests that a user can spend up to R150 a day. So a single user can be worth R700 a week to a dealer – R33 600 a year. “There is huge demand and prices are going up,” says Big Brotherhood member Vumani Khumalo. Msomi says 90% of the users they interviewed said they wanted out. “The more we spoke to the users, the more we could see that they were just people who were trapped.” Users and former users who have seen the play maintain that it is incredibly realistic in painting a picture of addiction. But Ulwembu is doing more than that.

It is asking us to face up to the realities that this is a community problem, and that it is going to require smart minds and a group effort to fix. “Who do you blame?” asks actress Mpume Mthombeni, who plays a user’s mother in Ulwembu. “It’s so easy to wash your hands, but what do we do with all this blame? This problem is all of ours.”

...

The story of Ulwembu goes back a few years, to May 2014 when award-winning Durban playwright Neil Coppen was heading a workshop with community-theatre participants from KwaZulu-Natal. He asked them to write lists of social issues that they felt young writers should be confronting in their work. The number one issue on everyone’s list was whoonga. “I had seen the whoonga problem mushrooming and taking over the city,” says Coppen. “I saw the way the media was reporting it, as a zombie apocalypse – people in rags around drums of fire – the nightmare of the suburbs ... We were dehumanising the users by creating these monster myths,” he told me.

During the workshop, then 22-year-old Phumzile Ndlovu shared a story about her cousin Jabulo, who had come to stay with them in Umlazi’s D Section. He soon became hooked on whoonga and was dealing the drug too. Her family, under threat from the community, had to throw him out and he relocated to Albert Park. He was addicted to whoonga for five years before he passed away at the age of 25. Driven by fears that his spirit would come back to harm the family, his corpse was beaten with sticks and then taken back to Albert Park, where whoonga was sprinkled on his lips and into his grave. The act was performed so that he could find peace. Coppen says it was this story that first lit the spark of what would become Ulwembu. After the workshop, he began to research the whoonga problem. “I spoke to everyone, from the hysterical white woman running the activist group to the business owner who was being broken into at night,” he says. “When I did interview the officials at the top, it was horrifying how little research they had done.” Realising that he was going to have to dig deeper, Coppen started looking for collaborators. “As a white male, I didn’t have access to the real story,” he says. “I could speak to social workers, but they all said the same sh*t, had the same statistics and inane files that actually said nothing ... They weren’t listening to the people going through it.”

...

The story of Ulwembu goes back a few years, to May 2014 when award-winning Durban playwright Neil Coppen was heading a workshop with community-theatre participants from KwaZulu-Natal. He asked them to write lists of social issues that they felt young writers should be confronting in their work.

The number one issue on everyone’s list was whoonga. “I had seen the whoonga problem mushrooming and taking over the city,” says Coppen. “I saw the way the media was reporting it, as a zombie apocalypse – people in rags around drums of fire – the nightmare of the suburbs ... We were dehumanising the users by creating these monster myths,” he told me. During the workshop, then 22-year-old Phumzile Ndlovu shared a story about her cousin Jabulo, who had come to stay with them in Umlazi’s D Section. He soon became hooked on whoonga and was dealing the drug too. Her family, under threat from the community, had to throw him out and he relocated to Albert Park. He was addicted to whoonga for five years before he passed away at the age of 25. Driven by fears that his spirit would come back to harm the family, his corpse was beaten with sticks and then taken back to Albert Park, where whoonga was sprinkled on his lips and into his grave. The act was performed so that he could find peace.

Coppen says it was this story that first lit the spark of what would become Ulwembu. After the workshop, he began to research the whoonga problem.

“I spoke to everyone, from the hysterical white woman running the activist group to the business owner who was being broken into at night,” he says. “When I did interview the officials at the top, it was horrifying how little research they had done.” Realising that he was going to have to dig deeper, Coppen started looking for collaborators.

“As a white male, I didn’t have access to the real story,” he says. “I could speak to social workers, but they all said the same sh*t, had the same statistics and inane files that actually said nothing ... They weren’t listening to the people going through it.”

...

So Coppen invited The Big Brotherhood, a community-theatre group he had worked with before, as well as actress Mthombeni, to collaborate with him. At this time, sociologist Dylan McGarry entered Coppen’s life. McGarry had recently completed a sociology PhD with a focus on empathy and he was interested in using theatre in the sociology and education fields. He conducted workshops with the actors, where they were trained in ethical research. “The idea of listening,” says McGarry, and pauses ... “listening is one of the most emancipatory things you can give. Listening is a gift. You are gifting someone your attention. But you also become a different type of listener – an active, empathetic listener. It’s all about them, not about you. Most people we worked with were so vulnerable. It had never been about them. That’s probably why they are users in the first place.” After training, the actors decamped to their own neighbourhoods in Umlazi and KwaMashu, and returned two months later with notebooks laden with detailed research. “Dylan calls them intuitive sociologists,” says Coppen. “Nobody could have got that level of access.” “Before, I thought all whoonga addicts were just criminals – people who would mug you and steal your phone,” says Mthombeni. “So imagine, now I had to approach these people and talk to them ... You need to think about how you approach the users in a respectful manner.” She says that, in a way, you are asking the user to undress in front of you in telling their story. “And then you realise these people have never been heard and are crying out for attention,” she says. “They are so relieved that they can pour out their problems to you.” Msomi says that the users respected that the actors came to them in a “neutral way”. “They want to stop smoking whoonga. They say they don’t know how,” he says. “They say the pain from the withdrawal, known as ‘arosta’, is so terrible they have to keep smoking.” It is most commonly the physically addictive opiate heroin, which is part of the whoonga “recipe”, that makes it so hard to kick. “These people have a problem that needs to be supported, not punished,” says Msomi. Ngcobo Cele from The Big Brotherhood says that the more whoonga users are judged, the more they feel as though they’re on the outside of society. “One guy I met was being bullied at school and then an older boy stood up for him. The older boy was smoking whoonga, so the younger boy started to impress the older boy. He was thinking: if I have this guy on my side, I won’t be bullied at school. A lot of it is all wrapped up in trying to be a hard man in the township, someone who commands respect.” The Playhouse run of Ulwembu last month also functioned as part of the research. “It takes in everything as it goes along and changes,” says Coppen.

...

After every performance, the audience is encouraged to remain behind in a facilitated discussion. It is loaded with users, people from rehabilitation centres, police, social workers, the homeless, sex workers, family members and former addicts. The conversations are lively and poignant, and loaded with testimony and sharing.

“They have a common reference point in the play,” says Coppen. “They are talking about the characters, not about each other. It takes away the personal. It’s about a deeper listening.” He tells of a previous performance where a senior police leader protested about a scene where the police make the users eat their drugs when they are caught. A whole group of users in the audience stood up and testified, one after the other, about how it had happened to them. After one performance, a 10-year-old street child speaks about how she is glad the mother character in the play did not give p on her son. The part that is implied, but remains unsaid about her own story, is heartbreaking for many. Another school teacher testifies how 12 kids in his class are using whoonga, and five are running the drug. To the cast, he says: “We need you desperately.”

Sam Pillay, head of the Chatsworth Anti-Drug Forum, says the play represents what he sees on the streets every day. He began fighting the rise of the designer drug “sugars” in his neighbourhood in 2005 and has been warning city officials about the extent of the problem for years. Professor Monique Marx from the Urban Futures Centre at the Durban University of Technology says they are trying to show government that it is cost-effective to roll out opiate-replacement therapy, such as methadone. She believes this should be coupled with the decriminalisation of the drug, a far better option than pushing whoonga underground. “Support, don’t punish,” she says, summing up her approach. Dr Lochan Naidoo, a Durban-based addiction consultant in the audience, says that by the time public health facilities implement methadone treatment for users, it will be too late, as happened with the roll-out of antiretrovirals. A middle-aged woman a few weeks out of jail after a nine-year drug conviction warmly thanks the cast and tells Cele, who plays Andile, a whoonga runner and user in the play, that she saw herself in him. “I was in tears here,” she says. “I was in that story.”

“Everyone has witnessed something together,” says McGarry. “And you have created a safe space for sharing.” In its essence, theirs is a continuation of South Africa’s vibrant protest-theatre tradition. The difficulty of black life is unpacked on stage to prompt social change.

...

At one point over the four days I spend with the cast of Ulwembu, I am sitting in The Playhouse foyer waiting for McGarry, who ran across the road to get some bean curries for lunch. He returned with the story of how a young guy from the street followed him into the takeaway joint and wanted to know more about the “whoonga play” that was on. McGarry told the young man he was involved and could get him a ticket. As we sit eating our curries in the foyer, the young man approaches to confirm his seat and thank McGarry. It’s clear that whoonga is all around us. We are all caught up in its web.

How do we make sense of the violent histories that mark our past? This play, Isidlamlilo, forces us to engage seriously with this question. Depending on your own relationship with our violent history, this play awakens a profound and at times unsettling realization that history is a living breathing force in all our lives. Isidlamlilo is set in the dying days of Apartheid, and in the present democratic South Africa.