Ulwembu (2014 - ongoing)

Over the course of 2015, a dynamic team of story-tellers, playwrights, theatre-makers, academics and researchers explored a growing concern on the rapid increase of smoking heroin in communities around Durban, in KwaZulu-Natal. Locally the drug is known as Whoonga, and is usually a concoction of B-grade heroin and a variety of other toxic chemical components. The result of the two-year research and play-making process was a powerful theatre production titled Ulwembu (isiZulu for Spider web). The creative team consisted of Neil Coppen, Mpume Mtombeni, Dylan McGarry and The Big Botherhood made up of Vumani Khumalo, Phumlani Ngubane, Ngcebo Cele, Sandile Nxumalo, and Zenzo Msomi. To create the script, the group listened to oral histories and testimonials from a broad cross-section of Durbanites, and transformed these accounts into an unforgettable documentary-theatre production on street-level heroin use in the city. Ulwembu provided a platform for transformative dialogue to take place around drug use, that engaged the empathy, intellects and imaginations of audiences by allowing them to follow a series of characters’ realities without judgment or prejudice. The play afforded local audiences the opportunity to walk in the shoes of misunderstood others as narrated through their own experiences: be it drug users, dealers, police-officers, social-workers or affected parents. Ulwembu was an integral advocacy component of a broader network of partners working on a harm-reduction approachto drug use in the city. Ulwembu went on to perform at the National Drug Policy Week and for members of the South African parliament.

Danger stalks the township of KwaMashu, near Durban. It comes in the form of Whoonga, which sucks its users into a vortex of addiction, crime, deception and personal tragedy that go with it. The Ulwembu of the title in isiZulu means spider’s web. Caught up in this web are the drug dealer, Bongani Mseleku; lieutenant Portia Mthembu, a police officer on the frontline of the fight against the scourge; her son Sipho, his friend Andile Nxumalo, and Emmanuel Abreu, a mozambique-born spaza shopkeeper. As it traces Sipho’s descent from talented scholar and aspirant musician to drug user, Ulwembu explores the effects of addiction not only on those who suffer from it but on communities, families and the police. It provides insight into how the different positionalities of those who try to control the murderous trade, those who benefit from it, and are harmed by it, are all part of a complex social web. Ulwembu is a theatre experience that asks important questions of our humanity.

During our two-year research process we researched the daily realities of police, parents, people who use drugs, the homeless, government civil servants, faith leaders, doctors, teachers and social worker. The core team met weekly for two years, sharing findings, stories, experiences, questions and ideas around the complex web that embodies not just Whoonga addiction, but addiction in general. The development of Ulwembu drew from a variety of theatre methodologies and genres, ranging from documentary, verbatim, forum, invisible and community theatre.

The devastating extent and complexity of Whooga addiction had increased at an alarming rate in Durban. Government and city officials, non-government organizations and other groupings struggled to combine forces and react with the speed and efficiency needed to respond meaningfully to the crises. Users had been widely pathologized in the city, experiencing a concerning lack of care and empathy. Frequently criminalized, users were dealt with in highly punitive ways by the police and different publics. The police tended to focus on operational strategies such as crackdowns, dispersal and heavy-handed law enforcement drives to deal with Whoonga users living on the streets. These punitive models contributed to the environments of violence in which the use of, and trade in, illegal substances could further expand. International research revealed that connection and care reduces harm and dissolves the risks associated with addiction much more successfully than punishment and criminalisation of the users. It was clear that in Durban a dynamic and empathetic forms of exchange and partnership was needed between government and civil society. There was a real need to open up the minds and thinking of the police, social workers, and health care practitioners, to consider drug use as a social and mental health issue, rather than a criminal one.

While the police in our interviews were aware of these problematic outcomes of punitive strategies, they battled to imagine alternative ways of responding to street level drug users. This was not the result of deficits in knowledge on the part of the police, but rather the result of the police being excluded from public health and solution-oriented networks. Police were reluctant first responders to whoonga addiction on the street. In a more robust harm reduction strategy towards drug use police are one (minor) tool in a broad range of social and health responses and interventions. The narratives performed in Ulwembu directly challenged existing responses and policy directives to street level drug addiction. The post-performance discussions created an invitation to collectively imagine alternative harm reduction frameworks that articulated positively with the recovery movement of drug users.

Exploring the sociological, political, economic, cultural, psychological and spiritual realities of drug use and recovery, changed us as individuals and as a ‘family’ of practice. Over the duration of its run Ulwembu was performed at a range of drug policy conferences, community meetings, church halls, open-days, homeless shelters, rehabilitation centres, universityies, state-of-the-art theatres, suburban art-galleries, and on one occasion, a children’s playground with the jungle-gym net improvised into the blocking of the play.

Ulwembu reached tens of thousands of people across South Africa, often settling in for longer theatre runs at institutions such as The Playhouse Loft Theatre (2016/2017) and UKZN SquareSpace Theatre (2015) in Durban, Hillbrow Theatre (2017) in Johannesburg, and the Theatre Arts Admin Collective (2018) in Cape Town.

One of the prerequisites of our project was that no audience member would ever be required to pay for their ticket, especially those without the financial means to do so. A generous grant from the Open Society Foundation (OSF) as well as additional support from the Urban Futures Centre (UFC) and the National Institute for Humanities and Social Science (NIHSS), enabled this.

Ulwembu not only impacted on the ‘doing’ of policing of street level drug addiction, as testified by police officers in the audience, but also contributed to broader organizational reform within police and health care organisations. The play went on to influence national drug policy, including supporting a pilot harm reduction programme in Durban run in collaboration with the Denis Hurely Centre, Urban Futures Centre and TB/HIV CARE.

Over the course of its run, Ulwembu garnered major publicity in South African broadcast and print media, making it onto SABC news inserts, Daily News lamppost headlines and front-page newspaper coverage. The production went on to scoop six of the thirteen categories it was nominated for at the 2016 Durban Theatre Awards—including Best Script, Best Newcomer, Best Director and Best Actress. In 2018, the play text was published by Wits University Press (Empatheatre & The Big Brotherhood 2018), and is currently available for study in local and international schools and universities.

The following scene is taken from the Ulwembu play text published by Wits University Press. In the below extract, Sipho Mthembu begs his dealer and school friend Andile to help him score another whoonga hit in the hope it will ease the debilitating withdrawal pains he is experiencing.

SCENE 10: OUTSIDE EMMANUEL’S SPAZA SHOP

Siphois lying on the floor clutching his belly, writhing around in terrible pain.

Sipho: Andile help me dog, please … help me. I’m dying from the stomach pain here. It hurts … it hurts so much.

Andile: Arosta.

Sipho: Ar … what?

Andile: Arosta. It’s part of the come down.

Sipho: What’s causing this?

Andile: The rat-poison in the goof.

Sipho: What?

Andile: The rat-poison leaving your system.

Sipho: You never told me we were blazing rat-poison!

Andile: The drug would kill us if we smoked it clean. The rattex is part of the mix … it keeps the blood flowing.

Sipho: How can I make it stop?

Andile: There’s only one way my bra.

Sipho: (Desperate) Tell me what it is … tell me.

Andile: You have to smoke more.

Sipho: More?

Andile: It’s the only way.

Sipho: Do you have any more on you?

Andile: Of course.

Sipho: Let’s blaze.

Andile: Not so fast Cheese boy … you’re going to have to pay up from now on. R25 bucks a hit. That’s four hits for a R100. That should keep you going for the rest of the day.

Sipho: What about the rest of the week?

Andile: You are going to have to find the cash for that.

Sipho: I don’t have any money.

Andile: That’s not my problem, bra.

Sipho: Ai Andile, help a friend out.

Andile: I’m not a charity, Cheese boy.

Sipho: (Begging) Please.

Andile: This is my business. My boss will kill me. You have to pay upfront from now on.

Sipho: I don’t have cash on me.

(Pause)

Andile: (He glances down at the new sneakers Sipho is wearing) What about those?

Sipho: These were a birthday present.

Andile: I’ll give you a week’s supply.

Sipho: Ai, voetsak! Once I get rid of this pain then I’m going to stop smoking this shit forever.

Sipho takes off his shoes and throws them angrily at Andile who collects his prize and examines them. Andile laughs.

Sipho: What’s so funny?

Andile: Ha! You think you can turn your back on whoonga just like that?

Sipho: (Clutching his stomach) Hurry up with that blaze man.

Andile: Your blood is dirty now, Sipho. You smoke once … twice … three times and you’re fucked! That’s why they call this intombi engaliwa.[iv]

He lights the joint for Sipho and hands it to him. Sipho smokes.

Sipho: You’ll see. I’ll give her up.

Andile: Not before she steals your cash … breaks your heart … and leaves you in a gutter.

Sipho: I’m not weak like you, Andile.

Andile: Every morning I wake up and say: “No more … today I’m done with this.”

Sipho: I have my whole life ahead of me.

Andile: That’s what we all say.

Sipho: I’ll do it!

Andile: You think you’ll be able to ignore it….

Sipho: You’ll see.

Andile: … you think that the pain will just go away? No it will only get worse, this is an eat-sum-more!

Andile rises and begins to rap in Zulu. Music underscores the sequence.

Andile: Ebumnyameni ngibona ifu elimnyama, isis sidungekile kugijima inynkalankala, Kuthi Khala inhliziyo ibencane. Aliko icala lomzimba elingabuthwele ubunzima. Amathumbu ayadonseka Afuna ukuphuma kulo owami umqala ngithi qala amehlo athifilifili, angizifili kulo owami umziba usuphenduke isidindi. Ngizothi umangikhala ngikhale ngiziwe ubani, Ngoba ebumnyameni ngibona ifu elimnyama.

The company, wearing balaclavas, slowly enter the stage and circle ominously around Andile wrapping long pieces of rope around his belly before moving to positions on opposite corners of the stage. As their grip gradually tightens, the ropes fasten painfully around Andile’s stomach. Sipho watches on.

Andile: (Grimacing) And you find that all you can think about is intombi, intombi, intombi engaliwa. And soon you realise that nothing will make the pain go away except … smoking more.

Andile takes the joint and inhales with desperation. The ropes relax and slacken around his stomach, falling to the ground. He is overcome with relief.

Andile: But whoonga costs money, ne? It doesn’t just grow on trees. So first you pay 25 rand for one hit. In the beginning you need one hit a day but as your body gets more and more used to it you start to need two and the next week … four. And soon 25 bucks becomes 50, then 100, until finally you having to find R150 bucks a day to fund your goof.

Sipho: Where the fuck am I going to find R150 a day?

Andile: The user always makes a plan mfana. It’s all about the hustle, my bra. (Strikes a pose) Allow me to introduce you to Andile Nxumalo’s survival guide to ensure you remain well and truly gooft in KwaZulu-Natal in the 21st century. (Andile begins miming the actions of the next sequence bringing them to life with comic flair). There are many ways you may choose to source this sort of income such as … (Pause) working as a caddie there by Greyville golf-course on Saturdays …

Sipho: I don’t know anything about golf.

Andile: Ai, relax boy. All you have to do is carry the clubs around for the gqonqa[vii] who are too lazy to do it themselves. Smile at the Baas politely and always congratulate him after each shot … saying things like (Putting on accent) “What brilliant aim you have Sir! or, “Excellent shot.”

They get tipped and blaze up.

Andile: Or you can help carry the Gogo’s groceries at the Bridge City Mall. (They re-enact the scene) Be polite … greet them warmly … remind them of their favorite grandson. Tell them you are saving up to invest in your university education for when you graduate from high school. (pause) Although there is always the point where you come short. This is where you going to need to start taking some chances mshana.

Sipho: How do you mean?

Andile: When I first started smoking whoonga, I used to steal meat from the delivery truck at the stop street and then sell it to people in the township for half the price.

Sipho: You mean breaking the law?

Andile: When your stash is running low … that, my friend, is when you need to have a “quick-fix” emergency plan.

Sipho: Emergency plan?

Andile: It is at this point that I should tell you about what is known by the user as “isikwhebu”[xi] … I’m talking minimum effort for a maximum high. Everything you see around us can be transformed into quick cash and more goof. It’s called isikwhebu.

Sipho: Isikwhebu?

Andile: (Listing the many options) Sound system shoes ungayshiyi ne ayina. Playstation fone nezingubo, ntshontsha ngisho ipenti kulayini... Hayi angikaqedi... ntshontsha nama grosa ekhabetheni ngisho umtwana umtwana omcane elele umnqume izitho siyozidayisa thina sife ukubhema Mfana sife ukubhema.

Andile gets more and more high, as he points out all the possibilities for financing his habit, and eventually collapses to the floor with Sipho.

Andile: (Laughing deliriously) Soon you won’t care if it’s your own mother you are stealing from …

Portia calls frantically for Sipho from off stage. Andile vanishes.

“ULWEMBU is a gritty urban nightmare, a place where characters mostly on the margins of society eke out lives, rather than live them. It is a story about addiction, featuring drug users, runners and dealers, desperate mothers, absent fathers, helpless and vindictive police, overworked social workers, enraged communities, fearless xenophobes and foreign nationals living in fear. It effortlessly illustrates how everyone in a community is drawn into the web of Whoonga. Large ropes pulled by the whole cast to contort around the users as they go into withdrawal represent this web.”

City Press

“Not only does ULWEMBU present an utterly compelling theatre experience, but it's true-to-life format means that this team is taking the bull by the horns and using the Arts to take to the frontlines of the war against drugs.”

Independent Online.

“ULWEMBU tells the story of the devastation and misery that is being wrought on our communities by the drug that goes by the rather amusing name of Whoonga. Ulwembu is the IsiZulu word for spider web and this insidious drug is exactly like that. Users are entrapped and there is no escape and soon the entire community can be affected by a vicious cycle of deceit, theft, violence and neglect. But this production is not a stereotyped “say no to drugs” play. It is a deeply-researched theatre project which is authentic, insightful, razor-sharp and frighteningly real. In fact, I would go as far as to say that this is educational theatre at its zenith.”

ArtSmart

“Directed with a muscularity and sense of conviction, this beautifully researched and deeply felt performance takes advocacy theatre which talks to the man on the street to a level that is considerably deeper and theatrically more developed than convention dictates. Normally, you might hear the words ‘community theatre’ or ‘advocacy drama’ and shrink away from the product’s aesthetic value, understanding it to be a mere one-dimensional extrapolation of bald ideologies. But the adjective ‘mere’ doesn’t fit in any understanding of this poignant and hard hitting play.”

Robyn Sassen, My View.

“I was profoundly touched by Ulwembu and its quest for humanity and dignity... there is no such thing as good and evil in places of survival …”

Professor Monique Marks, Urban Futures Centre

Not only does Ulwembu present a compelling theatre experience, but it's true-to-life format means that this team is taking the bull by the horns and using the Arts to take to the frontlines of the war against drugs.

Independent Online.

...this production is not a stereotyped “say no to drugs” play. It is a deeply-researched theatre project which is authentic, insightful, razor-sharp and frighteningly real. In fact, I would go as far as to say that this is educational theatre at its zenith.

ArtSmart Review.

Ulwembu powerfully reveals the root causes of substance abuse.

South African Police Service

If you are brave enough to hear what is seldom heard on an issue that touches rich and poor - then you need to let your heart be touched by this talented team ...

Father Tully, Emmanuel Cathedral

... this play challenges us, in a very graphic way, to face up to the human face of the problem and recognise that we do not know who it will hurt and how.

Raymond Perrier -Denis Hurley Centre

Audience feedback

“The play completely engaged my emotions. I felt great empathy for all of the characters. It brought overwhelming awareness of the vicious circle. I really need to do something about it.”

“I felt a sense of urgency. I felt a deep connection to those involved and affected by whoonga. I now realise how real it is, and I acknowledge my ignorance. I now see the issue for what it is.”

“… It was eye opening. It’s very easy to sit and judge and think addicts made their choice or chose to be addicts. The play gave me more empathy, understanding and less judgment.”

“It got me de-stigmatised. It made me think more about the users more than the problem.”

“Firstly I was shocked, then felt sorry for parents whose kids are affected by whoonga/other drugs. It inspired me to consider being more compassionate than judgmental.”

“…(I felt) horrified at first and now feel more empathetic to the man at the stop street. It’s deeper than a dealer problem.”

“The play brought tears to my eyes. As a recovered addict I could relate to everything the characters went through. It’s a difficult struggle and seeing it in the play touched me as I am so lucky to have had a parent who never gave up. In my darkest days of addiction, I even hit my mother. So to me she is the strongest most loving person I know.”

“I am a recovering addict and that’s the most realistic representation I’ve seen. It moved me to tears because I could relate to every moment.”

Researched, written and devised:

Neil Coppen, Dylan McGarry, Mpume Mthombeni, Vumani Khumalo, Phumlani Ngubane, Ngcebo Cele, Sandile Nxumalo and Zenzo Msomi.

Directed:

Neil Coppen

Design:

Dylan McGarry.

Lighting design:

Neil Coppen/ Dylan McGarry.

Sound Design:

Collin Peddie.

Score:

Braam Dutoit.

The project is led by Writer/Director Neil Coppen, actress/story-teller Mpume Mthombeni, Dylan McGarry (Educational Sociologist and artist) and The Big Brotherhood (Vumani Khumalo, Phumlani Ngubane, Ngcebo Cele, Sandile Nxumalo and Zenzo Msomi) in association with the Urban Futures Centre, Twist Theatre Development Project (Twist Durban), Think Theatre and the generous constant support of the Denis Hurley Centre.

Ulwembu has been primarily funded by the Open Society Foundations, as well as Twist (www.twistprojects.co.za), Urban Future Centre, The Playhouse Company, the Denis Hurley Centre, National Institute for Humanities and Social Science.

Ulwembu would not be possible without the support of Monique Marks, Kira Erwin, Emma Durden, Tina La Roux, Bryan Hiles, Margie Coppen, Kathryn Bennett, Rogers Ganesan, Stephanie Jenkins, Tamar Meskin, Raymond Perrier, Illa Thompson, Bongi Ngobese, Father Stephen Tully, Col. Vuyana, Pruthvi Karpoormath, Fathima Bi Bi Ally, Elena Naumkina, Cpt. Dingaan, Rob Chetty, Chris Overall, Commissioner Steve Middleton, Lloyd Gede, Greg Lomas, Carla-Dee Sims, Lynette Machado at Sad Sacks, Colwyn Thomas, Beata Bognar, Shaun Shelley, Val Adamson, Braam du Toit, Karen Logon, Iain (Ewok) Robinson, Don Fletcher, UKZN, DUT, Carrots; Peas at Kenneth Gardens, South African Police Services, Durban Metro Police, KZN Department of Health, City Press, Hillbrow Theatre and Gerad Bester.

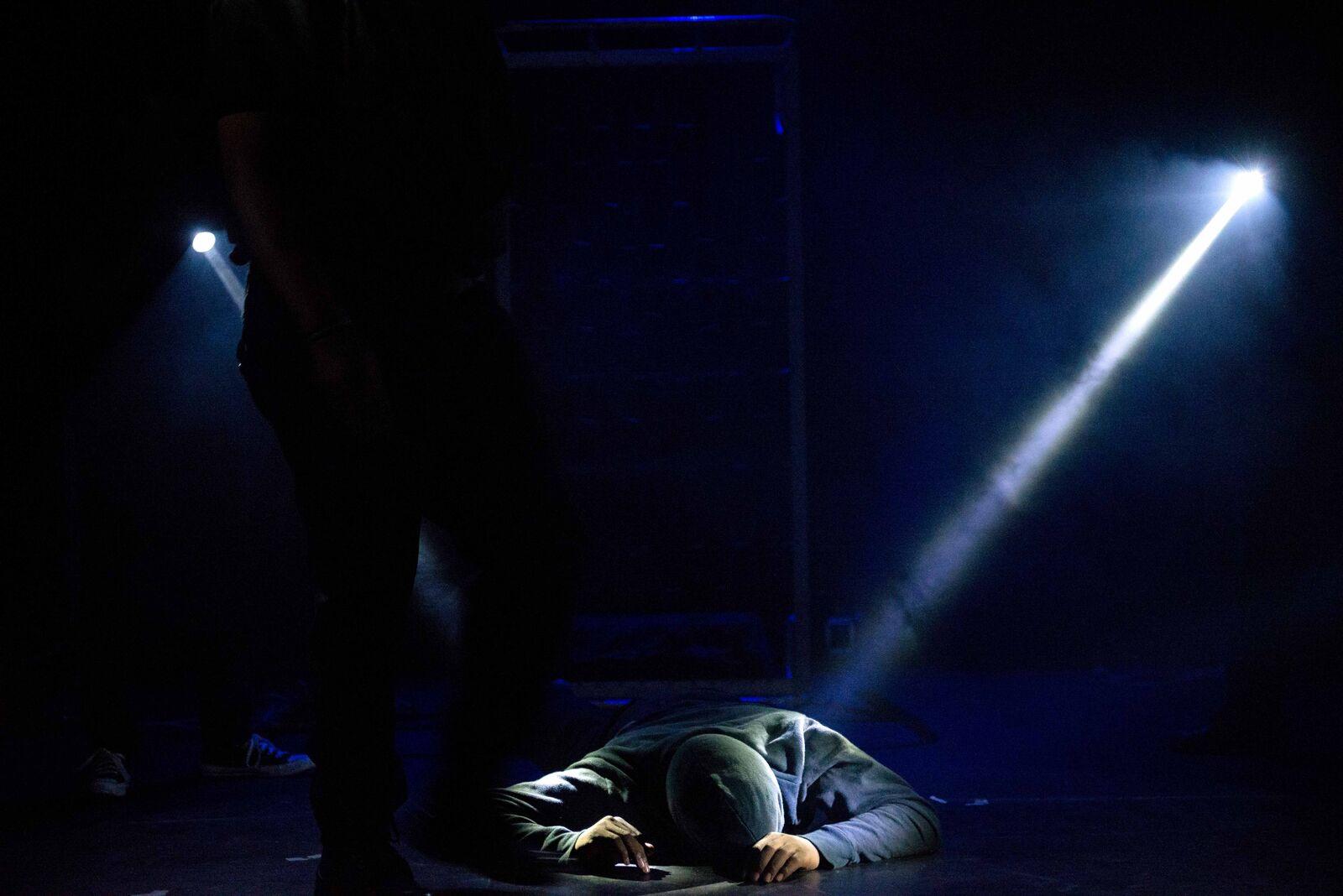

Over the duration of its five year run, Ulwembu was performed at a range of drug policy conferences, community meetings, church halls, open-days, homeless shelters, rehabilitation centres, universities, state-of-the-art theatres, suburban art-galleries, and on one occasion, a children’s playground with the jungle-gym net improvised into the blocking of the play. In this image, Portia (Mpume Mthombeni) attempts to get her son Sipho (Zenzo Msomi) to eat. The Handcuff scene is inspired by true events, where a desperate mother-- to protect her son from the community’s outrage-- handcuffed him to a bed for a month. Denis Hurley Centre community performance. 2016. Pic by Val Adamson.

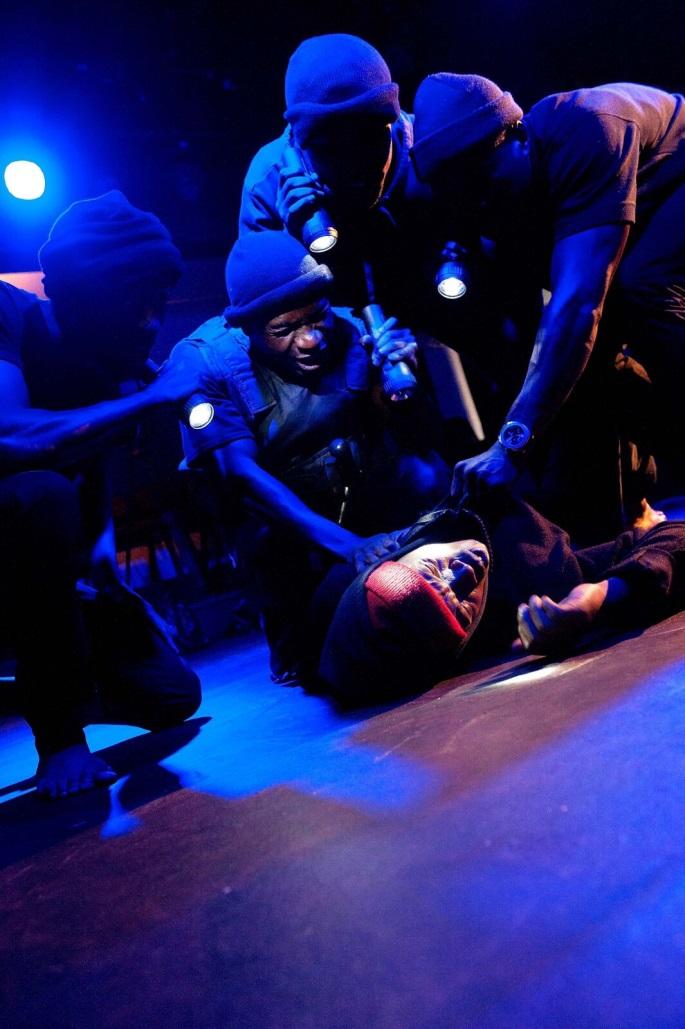

Ropes wielded by the cast, tighten around the waist of Sipho (Zenzo Msomi). The image helped us reveal the invisible pain caused by the side effects of the drug known as Arosta, but also to the interconnectivity of our community, and how the pain of one person will ultimately influence someone else. If we want to respond to drugs effectively in Durban, we need to respond to it collectively. Here the audience (a gathering of family members, health practitioners, users, and the police) watch the downward spiral of Sipho and Andile. Denis Hurley Centre Performance 2016. Pic Val Adamson.

Tangled ropes demonstrate the knot of intestines and painful cramps endured by Andile (Ngcebo Cele): “A dark cloud has settled over me. My intestines writhe and rise up through my neck. My vision blurs, obscured. I am no longer in my body. I melt into nothingness; I am brittle like grass in winter. If I cry who will hear me, a dark cloud has settled over me.” Rehearsal at Denis Hurley Centre 2015. Pic by Colwyn Thomas

Zenzo Msomi (Sipho) is handcuffed to the bed by his mother in a bid to help him come clean from the drug. Denis Hurley Centre rehearsal. 2015. Pic by Colwyn Thomas.

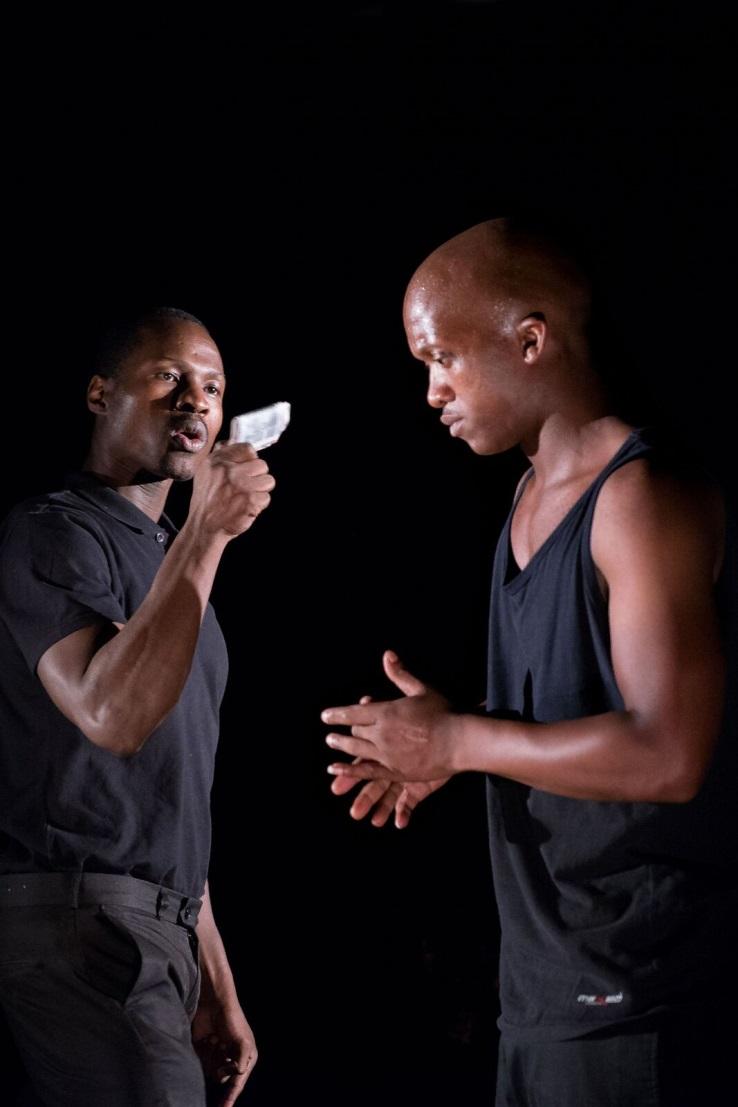

Whoonga dealer Bongani (Vumani Khumalo) faces off with policewoman Portia Mthembu (Mpume Mthombeni) in a tense scene from Ulwembu. Although Bongani had emerged from various interviews with dealers around Durban, the character’s real-life counterpart was identified by Mpume who, in the early stage of her research, began to interview a member of her community in Umlazi. Mpume had grown up in the same neighbourhood as the informant and this familiarity enabled her to deepen her friendship with him while breaching difficult topics in the interview process. As Vumani began to take ownership for the Bongani character, any further queries around his life story would be posed to Mpume who, after rehearsals, would revisit her neighbour and return the following day with further insights.

Playhouse Loft 2015. Pic by Val Adamson.

Ropes wielded by the cast, tighten around the waist of Andile (Ngcebo Cele). The name Ulwembu, which means ‘spider web’ in isiZulu, was chosen not just for its dramatic and perilous tenor, but as an apt image to capture the issues confronted in our play, which involved both the webs that ensnare us, and the potential for such webs to be a connective force, bridging gaps in our communities. Drawing insight from our spider web metaphor and referring to users’ testimonials around ‘arosta’—the name given to describe the painful withdrawal symptom including unbearable stomach pains that occur after smoking whoonga—we began to craft an image of connectivity and community, which would also suggest the crippling stomach cramps experienced by users. Playhouse Loft 2015. Pic by Val Adamson.

o achieve the arosta image, we began to experiment with two long ropes, held on either end by cast members, rising and ravelling around the belly of the narrating whoonga-using character. As the user’s cramps worsened, the company would encircle the character, pulling more tightly on the ropes as they went. This image not only articulated the harrowing physiological sensation experienced by whoonga users, but also suggested an arachnid spinning its victim deeper into the threads of its web. Here Andile (Ngcebo Cele) and Sipho (Zenzo Msomi) desperately try to rid themselves of the intensifying pain. Playhouse Loft 2015. Pic by Val Adamson.

In Scene 1 of the play, we witness the policewomen Portia (Mpume Mthombeni) bullying a hapless young dealer/user named Andile (Ngcebo Cele). Exhausted at the prospect of arresting the repeat offender, Portia oversees a cruel form or punishment whereby the police officers accompanying her, force Andile to ingest the contents of his whoonga ‘stash’. During the post-performance talk-back, one of the senior police officers in our audience took exception to this scenario, claiming it was sensational and untrue and an irresponsible depiction. Without our facilitator having to intervene, the policewoman’s comment was promptly met by a sea of raised hands in the audience and a range of testimonies offered by users who attested to the fact that this level of harassment was something they experienced on a frequent basis. If anything, one user in our audience had claimed, the aforementioned scene paled in comparison to the actual experience. Playhouse Loft 2015. Pic by Val Adamson.

Understanding the lives of users and police alike is complex, there is a real danger faced for both groups, and trying to understand the police's frustration and the user's desperation is a huge undertaking. Here policewoman Portia Mthembu (Mpume Mthombeni) interrogates drug runner Andile (Ngcebo Cele). Playhouse Loft 2015. Pic by Val Adamson.

The Ulwembu team spent almost a year ‘undercover’ interviewing users, dealers, police officers, doctors, social workers, ward councilors, parents, principals, teachers and friends in and around Durban (working more like sociologists than theatre makers). So far we have found that there are many ways out of drug use, but they require support from the community as a whole. What we have learned is that responding to drug use needs to be seen as a mental health issue and not only a policing issue. Playhouse Loft 2015. Pic by Val Adamson.

Sipho (Zenzo Msomi) in a scene from Ulwembu at the Playhouse Loft 2015. Pic by Val Adamson.

Ngcebo Cele (Andile) is arrested and forced to eat his stash by local police force. Playhouse Loft 2015. Pic by Val Adamson.

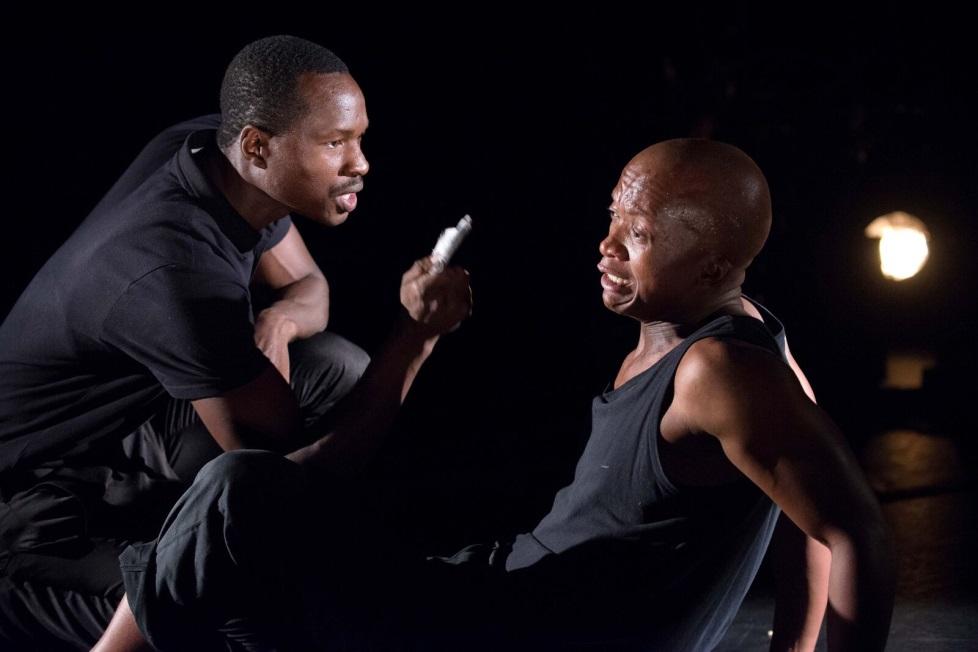

Zenzo Msomi (Sipho) and Ncegbo Cele (Andile) begin experimenting with a new drug outside Emanuel’s Spaza shop.

Playhouse Loft 2015. Pic by Val Adamson.

Zenzo Msomi (Sipho) and Ncegbo Cele (Andile) from the Big Brotherhood empathetically capture the lifeworld’s of young

men who are trapped in the grips of a Whoonga addiction. Playhouse Loft 2015. Pic by Val Adamson.

Ngcebo Cele (Andile) and Zenzo Msomi (Sipho) embodying the painful cramps known as "Arosta". Playhouse Loft 2015. Pic by Val Adamson.

Ngcebo Cele (Andile) and Zenzo Msomi (Sipho) embodying the painful cramps known as "Arosta". Playhouse Loft 2015. Pic by Val Adamson.

Sandile Nxumalo as Mozambiquan character Emmanuel in a scene reflecting on the xenophobic attacks in Durban which were conflated with the Whoonga crisis by the attackers. The tension between foreign nationals and South Africans has been exacerbated by the complex effect Whoonga has had on Durban. Understanding this effect requires real investigation as the issues are far more nuanced and powered by many myths and half-truths. Playhouse Loft 2015. Pic by Val Adamson.

Whoonga dealer Bongani (Vumani Khumalo) berates Andile (Ngcebo Cele) for smoking the goods. As with Portia and members of the police force, the character of Bongani enabled us to subvert stereotypes commonly associated with drug dealers. The story Mpume had uncovered was the story of a twenty-something year-old man, arrested for a crime he had insisted he did not commit. As a result, he had spent four years in jail and upon release, was expected to resume responsibilities in his family home and provide for his whoonga-using sister and her four small children. With a criminal record and no employment prospects, the only viable career option open to him was selling whoonga. Furthermore, his time in prison had provided him with links to criminal networks that would enable him to access and sell the drug. The informant had explained to Mpume that his current vocation was his only means of ensuring his and his family’s survival. Playhouse Loft 2015. Pic by Val Adamson.

Bongani (Vumani Khumalo) with Andile (Ngcebo Cele). Bongani is based on the real life story of a Whoonga dealer living in Umlazi. In our research we found that first time ex-convicts are offered around R10,000 as a ‘starter-pack’ by a local network of dealers who are also ex-convicts, to set up their own franchise. Dealers we interviewed said they could pay this off within a month, and have a fully-fledged business within two weeks. Playhouse Loft 2015. Pic by Val Adamson.

The Empatheatre approach steers clear of shock or scare tactics. Instead, the preference is to grant participating practitioners and audiences the opportunity to walk in the shoes of misunderstood and marginalised others through engaging complex lived experiences, rather than perpetuating stereotypical or simplified views of social issues. By participating in such experiences and through carefully facilitated post-performance talk-backs centred around the ‘epiphanies’ of the play, spectators and participants—the oppressed and oppressor—are able to re-examine and reflect on their own realities, prejudices, perceptions and misconceptions. In this scene Zenzo Msomi (Sipho) and Ncegbo Cele (Andile) puff and pass. Playhouse Loft 2015. Pic by Val Adamson.

The issues that Ulwembu confronts look both at the webs that snare us, as well as potential for webs to be connective, and bridge gaps in our communities. In the above image Sizwe (Zenzo Msomi) begs Andile (Ngcebo Cele) to help him quit the drug. Playhouse Loft 2015. Pic by Val Adamson.

The character of policewomen Portia, played my Mpume Mthombeni, is an example of a composite character. Guided by Mpume, with input from the group, we created a mother character named Portia who also happens to be an ambitious and militant policewoman working in the streets of KwaMashu. Portia was contrived so that when we first encounter her in the play, she is likely to reflect and reiterate a majority of the audience’s own prejudices around drug users. Yet, as events take a dramatic turn, spectators are forced to empathetically re-examine and contest their own perceptions alongside her.

In this scene Portia (Mpume Mthombeni) attempts to nurse her son Sipho (Zenzo Msomi) through an involuntary detox. Playhouse Loft 2015. Pic by Val Adamson

ortia (Mpume Mthombeni) attempts to urse her son Sipho (Zenzo Msomi) through an involuntary detox. Playhouse Loft 2015. Pic by Val Adamson

Desperate prayers from the Church congregation during the painful detox of Sipho Mthembu (Zenzo Msomi) as his mother (Mpume Mthombeni) watches on. Faith based organisations have a profound role to play in responding to the drug crisis in Durban. The Denis Hurely Centre and Emmanuel Cathedral have been actively responding to the health and wellbeing of many street level users, many of which are homeless, hungry and need of medical attention. Playhouse Loft 2015. Pic by Val Adamson.

To learn more about the pathways out of Drug use, we set a new research task, which involved the actor-ethnographers heading out into their communities and searching for inspiring narratives of users rehabilitating from whoonga use and successfully integrating back into society. Such narratives were, however, few and far between. Rather, we discovered that a range of approaches would need to be acknowledged as the ‘solution’. In this scene Zenzo Msomi (Sipho) discovers the body of Andile (Ngcebo Cele). Playhouse Loft 2015. Pic by Val Adamson.

Portia (Mpume Mthombeni) shares her story at a support group: “We are taking it day by day now, we try to be more patient, more gentle with each other. We share our stories and we listen to others and by listening….we begin to heal.”

Playhouse Loft 2015. Pic by Val Adamson.

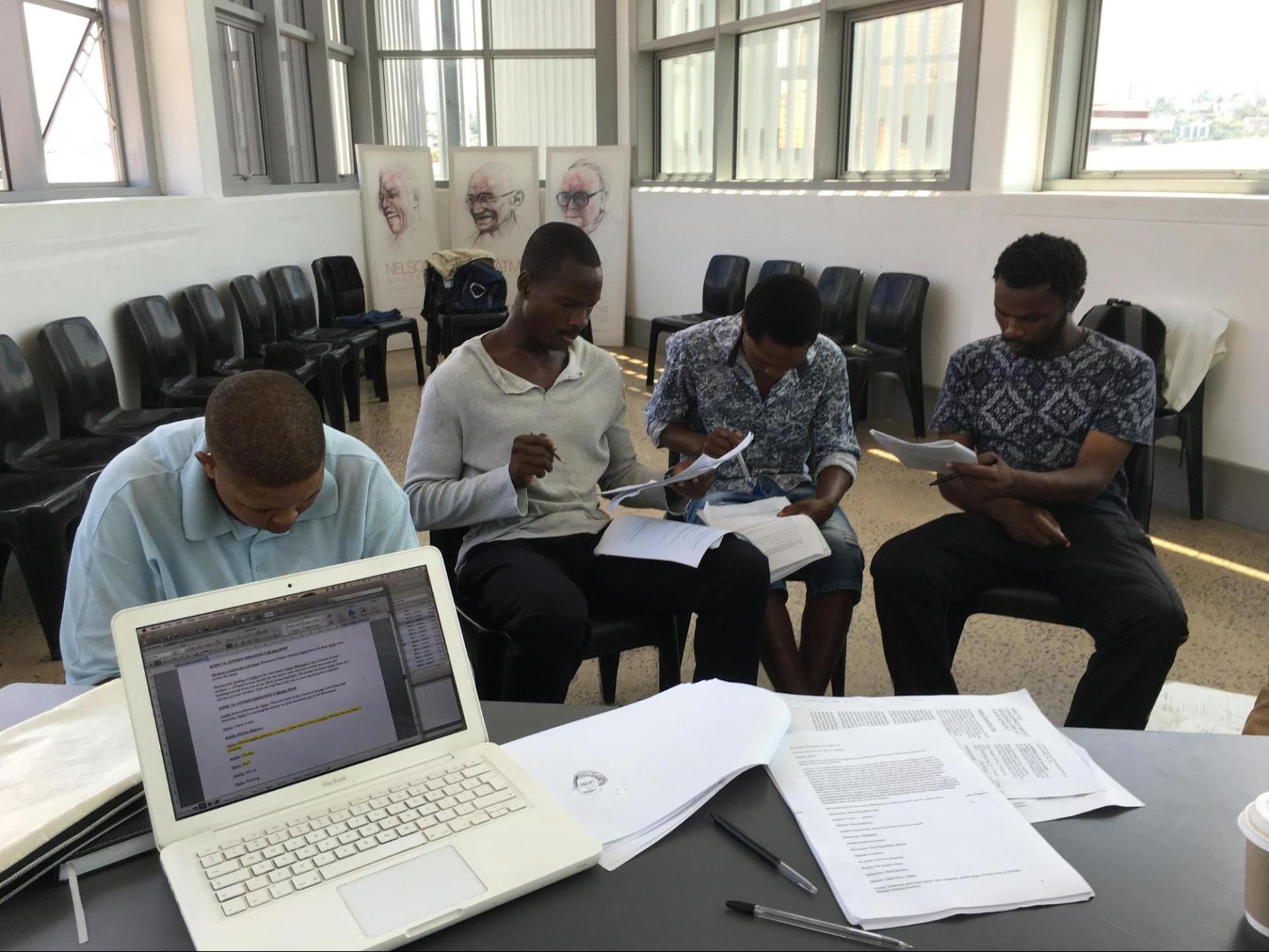

Before embarking on the research for what would come to be called Ulwembu, Dylan—drawing on his sociological academic background—guided the team through a discussion on the ethics behind participant observation and generative reflexive research techniques. Other areas covered included how to document field notes and correctly translate and transcribe interviews. During these workshops, we also urged the team to work in groups of two and prioritise their safety by steering clear of threatening situations, particularly when it came to interrogating the more covert networks of whoonga manufactures and dealers. Here the team meet at the Denis Hurley Centre to reflect on their findings.

The Ulwembu family: (left to right) Mpume Mthombeni, Zenzo Msomi, Phumlani Ngubane, Sandile Nxumalo , Ngcebo Cele, Vumani Khumalo, Dylan McGarry and Neil Coppen. To create the script for the production, the group listened to oral histories and testimonials from a broad cross-section of Durbanites, and transformed these accounts into an unforgettable documentary-theatre production on street-level heroin use in the city.

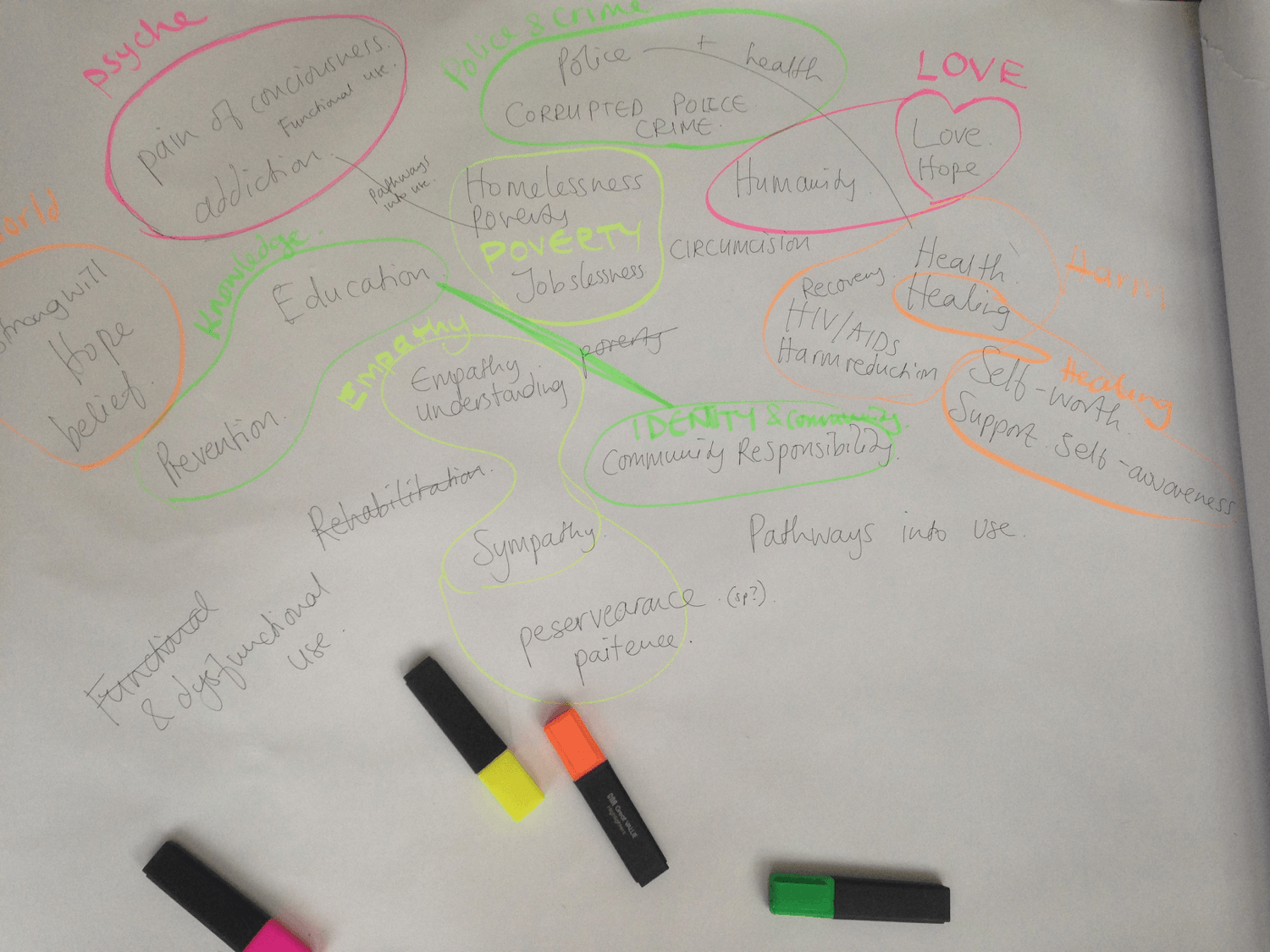

During the devising of Ulwembu we set about listing associated words and ideas on a white board. In this session the words: love, hope, community, responsibility, perseverance, patience, healing, prevention, humanity, self-worth, poverty and empathy, spanned the expanse of our paper. When we began to individually prioritize these words, the word empathy remained at the top of our respective lists. What did empathy mean to us? How had the empathetic connections we had all forged with a range of informants transformed our own preconceived ideas around street-level drug addiction? How would our play subtly work to stimulate a similar set of responses and discoveries in our audiences? These were all questions that were posed and discussed at great length. As we grouped our interrelated ideas with the help of color-coded highlighters, we discussed the need for the theatrical experience we devise to, first and foremost, empathetically address misconceptions, turn stereotypes on their heads and offer audiences innovative and new ways of seeing and comprehending the issue.

A scene from a public performance of Ulwembu at the Edendale Rehabilitation center in Johannesburg. During this performance at a center used for rehabilitation work in Edendale, Johannesburg, our audience included police, a wide range of users enrolled in a rehabilitation program and high-school learners from a nearby school. In this particular session the actors and facilitator took a backseat allowing for a conversation to occur more directly between the learners and recovering users in the audience. In this instance, a range of impassioned recovering users assumed the role of facilitators and educators, answering a variety of questions posed by the learners and members of the police, while using the plays characters and narrative as a means to prompt and reflect on their own experience with addiction.

Ulwembu is a collaborative documentary-theatre project, that brings together writers, theatre-makers, citizens and civil society to engage the interface between street-level drug-addiction, policing and mental health in the city of Durban, South Africa. Here director and co-writer Neil Coppen talks Zenzo Msomi (Sipho) through a difficult scene. Denis Hurley Centre rehearsal Room 2015. Pic by Colwyn Thomas.

Designer/co-writer and sociologist Dylan McGarry working alongside Menzi Mkhwane at the Denis Hurley Centre rehearsal Room. 2015. Pic by Colwyn Thomas.

Actors Zenzo Msomi (Sipho) and Ngcebo Cele (Andile) from the Big Brotherhood work on the Arosta scene while team members Neil Coppen and Dylan McGarry watch on. Denis Hurley Centre rehearsal Room. 2015. Pic by Colwyn Thomas.

Ulwembu is not merely a precautionary play that aims to ‘scare’ young people into not using drugs. The life of a whoonga user is scary enough; there is no need to add to that horror. Instead the production goes beyond intimidating audiences into avoiding drugs, but rather revealing the entire world of drug use in the city, and to create an engrossing, emotive and honest experiences for audiences, that speak to the realities of why people begin to use drugs in the first place. Zenzo Msomi (Sipho) in rehearsal with Mpume Mthombeni (Portia) at the Denis Hurley Centre 2015. Pic by Colwyn Thomas.

Big Brotherhood actors recreate the scene where Sipho (Zenzo Msomi) is arrested by Police, for director Neil Coppen. The Denis Hurley Centre. 2015. Pic by Colwyn Thomas.